<<<<<

Reduction/Abation

redirect the air: fabric installation

insulation: moss wall

Adapting to the Noise: workshop/intervention

making other sounds: countered by music

--> noise on top of noise

ear cleaning exercises: decolonial, collective listening

--> question wilderness, racialization of noise

recording the sound, cassettes

--> replay somewhere else

vs

-

-

-

-

-

Bass thumping through the walls from a neighbours party, the soft whirr of a computer when it overheats, rain pattering on a window pane; there is always some kind of noise around us. Even while writing this paper, the sentences have been shaped by neighbours’ construction work until late in the evening, the soft whoosh of a vacuum cleaner down the hall, the clacking of another student typing on their keyboard in the library. Yet, these noises are all distinct, affecting each of us differently in various contexts. We all know that familiar feeling when you become hyper focused on a noise, like the ticking of a clock, stopping at nothing to figure out where it comes from and shutting it off, while other nights you don’t even notice it, or maybe even find that its rhythmic clacking lulls you to sleep. The term noise here holds multiple meanings, metamorphosing to fit different situations and listeners.

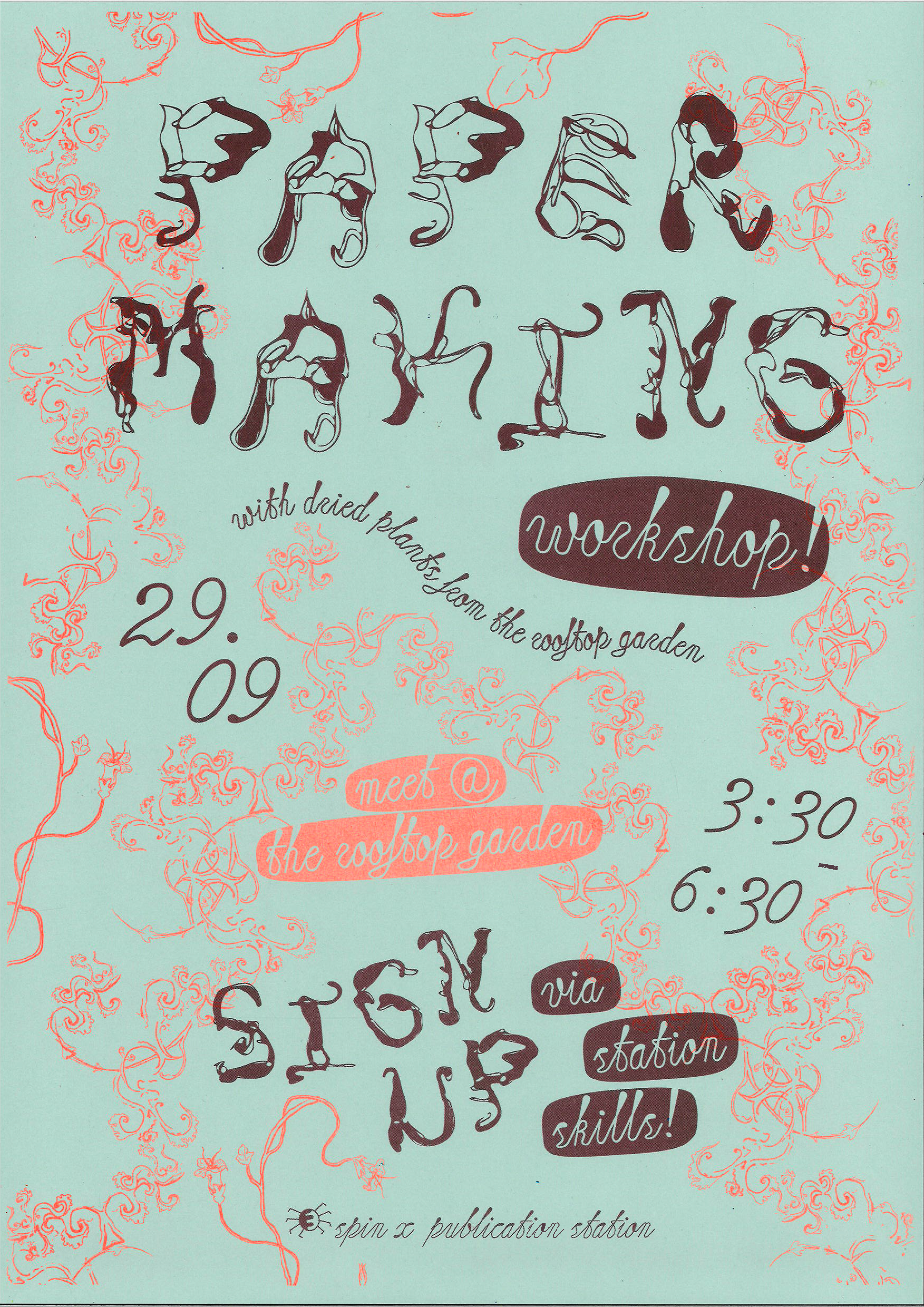

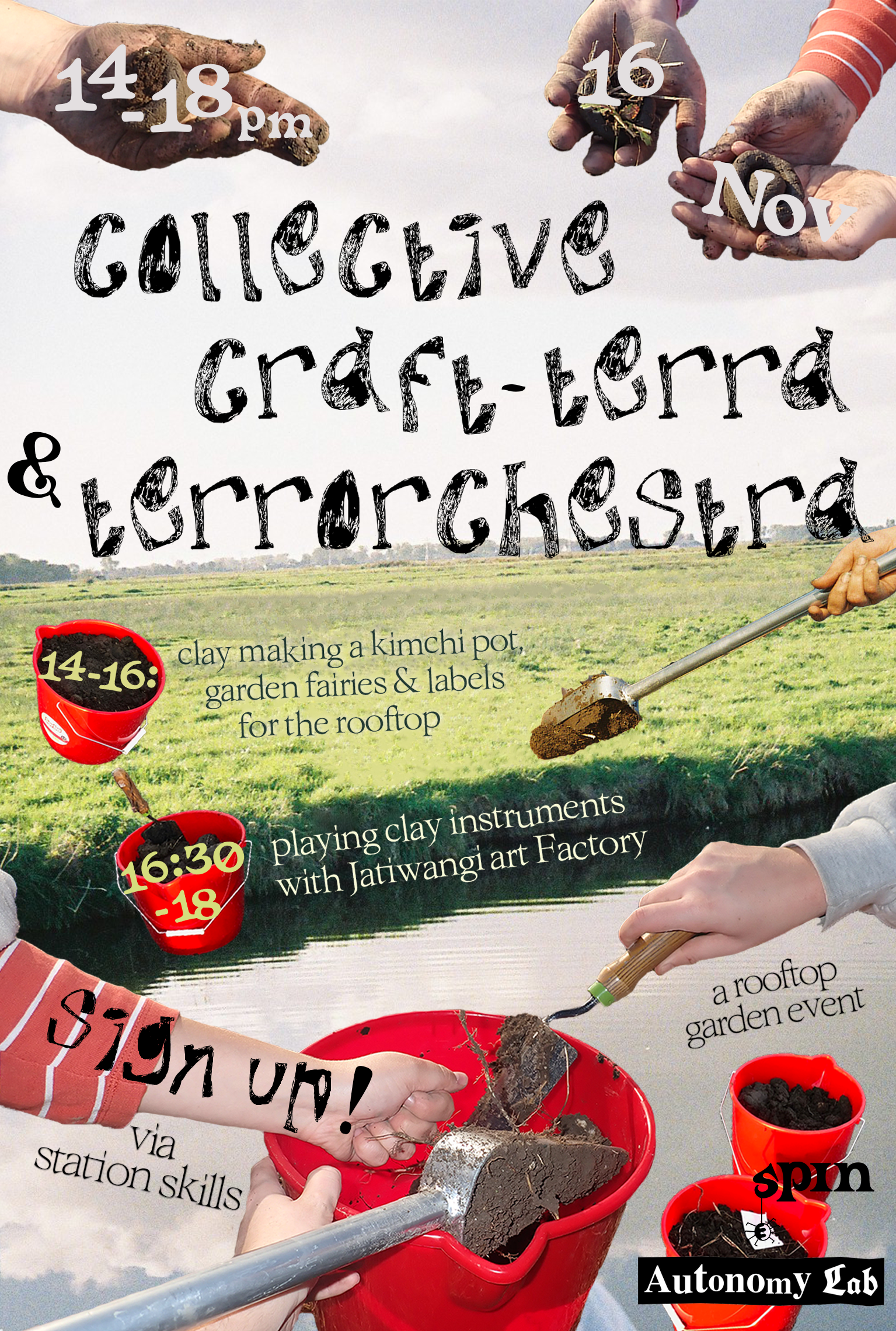

This project originated as an investigation into the noise of a constant hum of air being released from a ventilator on the rooftop of the Willem de Kooning Academy (WdKA). Together with fellow members of SPIN, a student-led climate justice collective at WdKA, we have started transforming this rooftop space into a garden that we intend to use not only to grow plants or start a compost, but also as a space for students to meet or use for projects. To start the process of setting up this rooftop garden we have been organising several events around the pagan holidays as a means of bringing the community together through collective dinners, musical concerts and workshops that surround building up the space. One such event was a movement workshop with Lotte van Gelder to physically connect with the building, but it was very difficult to hear Lotte’s instructions over the hum of the ventilator fan. Thus, the initial aim of this project was to figure out how to diminish or even get rid of the noise as it was disturbing not only our events but any future activity on the rooftop garden. This process began by mapping out a soundscape of the space, measuring noise levels in different areas to better understand how the sound travels throughout. The result of this mapping is included on the inside of this publication as a poster that can be unfolded.

However, while reading further into noise as a concept, the goal of noise abatement soon shifted. A crucial piece of information from our events had been overlooked; during the concerts, the noise seemed to fade into the background, no one was complaining about not being able to hear one another, the focus had been pulled to the musicians on stage. The realisation that we had been taking a one-sided, hegemonic approach to noise as something unwanted, annoying and chaotic became clear. As a result, this paper attempts to argue for a more nuanced understanding of noise as a medium, a relation, a means of communication that transcends binary, dualistic conceptions. This will be done by first deconstructing the common misconception of noise as solely unwanted and bad to develop an understanding of noise as a relation by examining the dualisms of noise/silence, noise/music. Therefore, unpacking the moral associations and implications of noise enables an embrace of an understanding noise as something that exists within, against and beyond capitalism, providing an opportunity for a transformation of relations. Understanding noise in this manner calls for a different practice of listening, decentring the listening subject to focus on the mode of perception which is embodied and situated in the present context, enabling noise to be seen as a means of communication that goes beyond the discursive realm.

Introduction

Deconstructing Noise

When seeking to grasp the prevailing connotations of noise as something ‘bad’, unwanted and nonmusical or nonlinguistic, its relationship with affect is useful since noise often instigates a negative emotional response from listeners (Thompson, p.10). The term noise even stems from the Latin ‘nausea’ referring to seasickness, further illustrating how “noise is often felt as well as heard” (Thompson, p.11). Here, noise is seen through dualisms, opposed to ‘good’, desirable sounds like music, or in other words, more intentional information. This demonstrates the subject and object-oriented definitions of noise such that the former relies on a judgement by the listener of either wanted or unwanted, good or bad, and the latter on the sonic qualities of the sound itself as either music or noise, natural or unnatural (Thompson, p.23). The statistical notion of noise as variation or error that originates from the law of large numbers in calculating probability and opposes noise to data, problematizes the clear-cut distinction between these two definitions, and their claim of noise as solely unwanted (Malaspina, p.1). This perspective of noise as a source of uncertain, accidental change is not always considered a disturbance to the collection of data, but can also become information itself, constructing new knowledge and thus something ‘good’ (Malaspina, p.2).

The separation of subject and object-oriented definitions of noise is unsettled even further since unwanted sound is generally emanated from an unwanted source, intertwining the two (Thompson, p.26). This demonstrates noise as a sociopolitical issue of power that involves the determination of what is and is not considered noise, and consequently, how it should be regulated (Malaspina, p.145). The arbitrary distinction between sounds has served to fabricate a differentiation between ‘Other’ and subject, human and non-human, colonised and coloniser, civilised culture and barbaric nature (Thompson, p.28). These divisions derive from and are upheld by racist, colonial and heteropatriarchal capitalism (Castellanos, p.157), such that “sound functions as a set of social relations” (Stoever, p.3). For example, Black music is deemed unintelligible and chaotic, similarly, women are seen as chatty gossipers, both meaningless noises as opposed to the dignified silence of white men (Thompson, p.28). Here, the invisibility and inaudibility of white masculinity as the prescribed, hegemonic norm or standard is made apparent, associating silence with nature in contrast to loudness (Stoever, p.6). This paradoxical use of noise to silence certain voices and bodies further problematizes the apparent unwantedness of noise, since it is, in a way, wanted here as a means of demonstrating power. However, this relation is situated within a particular sociopolitical context or moment in time and space, it is not static but rather constantly changing (Thompson, p.47). Thus, due to the varying characterizations of and moral associations to noise depending on its source and environment, when understanding noise one must not focus on what is being perceived, but rather the act of perception itself (Malaspina, p.162), calling for a new practice of listening.

Practices of Listening

When thinking about developing a new practice of listening concerning noise, it is useful to consider Schafer’s notion of acoustic ecology, which conceives of noise as a problem that disrupts the ‘naturally’ quiet soundscape (Thompson, p.88). This dualist aesthetic moralism views silence as a rare, calm and good phenomenon that has been ruined by noise pollution, thus romanticising the optimal soundscape as existing in the past, before the harsh sounds of machinery from the industrial revolution (Thompson, p.92). He thus proposes a practice of listening that focuses on resensitizing the listener, who should learn to appreciate their noisy acoustic environment through ear cleaning exercises or sound walks that aim to enlighten them about the negative effects of noise (Thompson, p.90).

Similarly, avant-garde methods of making music aimed to rethink how we listen to and interpret noise. The Dada movements’ ‘bruitism’ that embraced noise as a form of music questions the listeners' understanding of noise as something nonmusical, attempting to integrate it into the realm of the musical (Kahn, p.45). John Cage’s infamous silent composition entitled 4’33 goes even further than bruitism by inducing a shift in music production from focusing on its site of production to how it is being heard (Kahn, p.158). By bringing the background noises that are always present during a performance to the centre of attention, Cage questions the distinction between music and noise as well as noise and silence by merging art and life, he “proposed a mode of being within the world based on listening, through hearing the sounds of the world as music” (Kahn, p.161).

Schafer’s and Cage’s approaches to silence both highlight the listener as the subject who should alter their mode of listening to develop a new understanding of noise, yet they have opposing definitions of silence. Where Cagean silence consists of unintentional sound no matter how loud (Kahn, p.163), for Schafer, silence is complete quiet, associated with pure and untouched nature (Thompson, p.115). Consequently, while both Schafer and Cage claim to embrace noise and silence through positing new practices of listening, they actually end up enforcing the dualistic, moral associations of noise; Schafer dictates how one should interact with sound through the body and delimits noise as inherently bad, and through bringing focus to noise and silence, Cage ends up silencing the musical performer, creating a new set of restrictive social regulations of listening.

A more nuanced practice of listening that builds upon Schafer and Cage’s focus on the listening subject has an understanding of noise as transcending hierarchical binary oppositions with moral connotations at its core. This involves a decentring of the listening subject as the sole constituents of noise, and an understanding of noise as a productive force (Thompson, p.54). Shannon’s Mathematical Theory of Communication shown above presents noise as a relation, a force that holds the power to influence and affect; “noise is what noise does” (Thompson, p.51). Rather than solely disrupting or inhibiting communication, noise is also an affective medium constituting relations, such that it enables communication by carrying information (it is affected) while simultaneously modifying what it contains (it affects) (Thompson, pp.61-62). This model of noise allows it to exist as a relation between both sides of the dualisms of good/bad, silent/loud, and music/noise, while functioning as a simultaneously destructive and constructive force of knowledge. Thus, in Thompson’s words, noise “is not ‘either/or’ but ‘both-and’, traversing distinctions” of binary oppositions (p.8).

This transcendence of hegemonic dualisms reveals an underlying revolutionary dimension of noise as political resistance, as an opportunity for a transformation of the biassed system of representation from within it (Thompson, p.178).

“Noise is never far away from proclamations of its ability to unsettle, uproot or overturn established musical orders and sociopolitical codes”. (Thompson, pp.176-177)

However, whilst theorising this political potential of noise, it is important to pay attention to the inevitable co-option of this resistance by capitalism into something profitable (Thompson, p.177). Listening will thus necessarily exist as a practice of “listening to, listening for, listening through, listening in, listening out, listening over, listening with [and listening against]” (Helmreich, p.10).

By situating an understanding of noise as embodied both within subjects (human or nonhuman) and within a specific social, political and historical context, listening becomes an affective practice, involving not only the ears but the entire body and its current environment (Castellanos, p.166). Castellanos proposes a decolonial form of listening that he defines as “the act of listening turned into a philosophical act of questioning” (p.160). He suggests that since listening properly involves actively taking part in and allowing oneself to experience and be inhabited by sound, in doing so one risks difference, risks crossing the established borders of self and Other (p.166). Here, the collective is prioritised rather than the individual as a means of shattering and existing beyond the subject/object, good/bad, music/noise dualisms.

Developing a Noise Strategy

“When you can’t destroy the buildings, change the sound, change the listening”.

(Holmboe, Haxholm, & Kirstein p.16)

So far, this paper has deconstructed the common notion of noise as something inherently unwanted and bad, to present a more nuanced understanding of noise as a medium, a relation that requires a new form of listening which appreciates its complexity and potential for political resistance as means of transformation through a simultaneous construction and deconstruction of knowledge. Applying this complex, situated and embodied understanding of noise and listening as ‘both-and’ to the noise on the rooftop garden at WdKA informs a more nuanced response strategy or plan that is not focused solely on noise abatement.

Such a plan would acknowledge and recognise that where the ventilator’s noise is disturbing in certain contexts, it is concurrently unnoticeable in others. Thus, a corresponding noise strategy could involve both lessening the noise, as well as transforming or engaging with it in different ways. The following speculative three-part plan has emerged as a result of this diversified understanding of noise.

In terms of noise abatement, a living moss and mycelium sound absorber panel could be installed on the walls that currently enclose the ventilator, as a means of diminishing the sound in a way that harmonises and integrates well with the surrounding ‘natural’ rooftop garden environment.

A possible engagement with the noise could play with the air that is being released from the ventilator, using it as a source of wind for musical instruments such as an aeolian harp or organ. This could take the form of an adaptable and removable sound installation above the moss wall, in order to have the possibility to evolve with the changing needs of the space and the community. This would be a means of intercepting noise with noise to influence and potentially transform the unwanted affective response it can have.

Lastly, as a means of connecting with and acknowledging the noise as a part of the space, an embodied, situated, relational and decolonial listening and noise workshop could be developed based on the values put forth in this paper. This would facilitate a more collective transformation and integration with the noise, and a means of connection between the noise and community, as well as within the community. Additionally, this would provide a moment for collaboration and discussion surrounding the community’s affective responses to the noise, and whether the noise strategy should be altered in any way.

Conclusion

Throughout this paper, the common misconception of noise as understood through binary oppositions of music/noise, silence/noise, wanted/unwanted, natural/unnatural has been deconstructed. When comparing different definitions of noise as subject or object-oriented, a contradiction emerges that reveals and clarifies and understanding of noise that is situated within a specific context. This calls for a more nuanced practice of listening, which Schafer and Cage posited in contrasting ways, yet ultimately showing the importance of an embodied form of listening. Shannon’s Mathematical Theory of Communication brings a final puzzle piece that demonstrates the affective qualities of noise to influence and be influenced. This presents noise as a relation and medium of communication that transcends dualisms, existing beyond the discursive realm of language and in the situated body.

The attitude towards noise and listening presented here will inform a series of experimentation towards developing a corresponding noise strategy. Currently, these experiments are based on the speculative proposal delineated in the last section of this paper, but due to their exploratory nature, can likely change in response to developments discovered throughout the trial process. These experiments and reflections upon them will be documented extensively online and can be found via the QR code included in this publication.

Bibliography

Beauchamp, A. (2015). Live through this: Sonic affect, queerness, and the trembling body. Sounding Out, 14.

Cronon, W. (1996). The trouble with wilderness: or, getting back to the wrong nature. Environmental history, 1(1), 7-28.

Castellanos, D. A. H., Toro, R. (2020). Decolonial listening. Sonorous bodies and the urban unconscious in Mexico City. Border-Listening/Escucha-Liminal (Vol. 1).

Helmreich, S. (2010). Listening against soundscapes. Anthropology News, 51(9), 10–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-3502.2010.51910.x

Holmboe, R., Haxholm, C., & Kirstein, T. R. (2018). Handbook of Aggressive Listening. Forlaget Forlag.

Malaspina, C., Brassier, R. (2018). An epistemology of noise. Bloomsbury Academic.

Stoever, J. L. (2016). The sonic color line: Race and the cultural politics of listening (Vol. 17). NYU Press.

Schafer, R. M. (1994). The soundscape: Our environment and the tuning of the world. Rochester: Destiny Books.

Thompson, M. (2013). Gossips, sirens, hi-fi wives: Feminizing the threat of noise. In Goddard, M., Halligan, B., & Spelman, N. (2013). Resonances: Noise and contemporary music. (pp. 297-311). Bloomsbury.

Thompson, M. (2017). Beyond unwanted sound: Noise, affect and aesthetic moralism. Bloomsbury.

Gallagher, M. (2016). Sound as affect: difference, power and spatiality. Emotion, Space and Society, 20, 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2016.02.004

Kahn, D. (1999). Noise, water, meat: a history of sound in the arts. MIT press.

feminist philosophy version: